It’s 2022 and you’ve just arrived at the travel destination of your dreams. As you get off the plane, a robot greets you with a red laser beam that remotely takes your temperature. You’re still half asleep after a long transoceanic flight, so your brain barely registers the robot’s complacent beep. You had just passed similar checks when boarding the plane hours ago so you have nothing to worry about and can just stroll to the next health checkpoint.

This pandemic will change the culture of how people are travelling

As you join the respiratory inspection queue, a worker hands you a small breathalyser capsule with a tiny chip inside. Conceptually, the test is similar to those measuring drivers’ alcohol levels, but this one detects the coronavirus particles in people’s breath, spotting the asymptomatic carriers who aren’t sick but can infect others. By now you know the drill, so you diligently cough into the capsule and drop it into the machine resembling a massive microwave. You wait for about 30 seconds and the machine lights up green, chiming softly. You may now proceed to immigration, so you fumble for your passport and walk on.

Airports in the future may have a respiratory inspection queue to detect coronavirus particles in people’s breath (Credit: Rarrarorro/Getty Images)

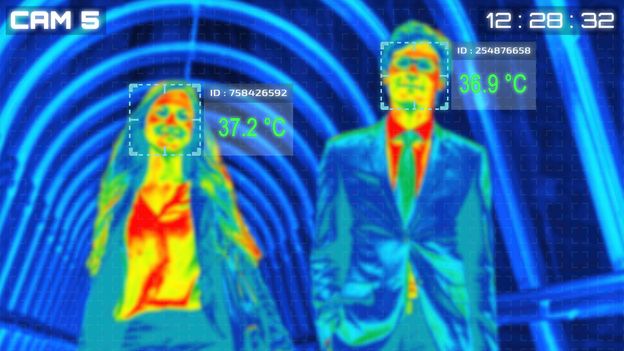

These technologies may sound like science fiction, yet they are anything but. If you had travelled earlier this year when countries began locking down, you may have already spotted the remote infrared thermometers used in airports. However, while thermometers are helpful, they aren’t ideal. People can have fevers for others reasons or may harbour coronavirus without symptoms. To spot early infections or asymptomatic carriers, one has to check for the coronavirus particles in their breath.

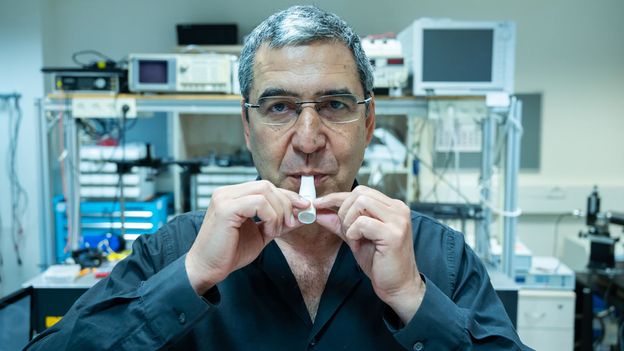

That’s where the breathalyser comes in. You haven’t yet seen it at transit hubs, but it already exists at the photonics lab of Gabby Sarusi, professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel. When Covid-19 struck and hospitals worldwide struggled to build fast and accurate biological diagnostic tests, Sarusi looked at the problem differently. As a physicist, he viewed the coronavirus’ spiky sphere not as a biological agent but as a nano-sized particle that can be sensed by specialised electrical equipment. When tossed into the midst of an electromagnetic field, the particles cause certain “interference” to the flow of electromagnetic waves, which can be detected. That’s what happens when the capsule is dropped into the microwave-resembling machine.

“We are taking the chip inside the capsule and we’re measuring it with a spectrometer that’s radiated with the magnetic waves,” Sarusi explained. If coronavirus particles are present, he said, “we can sense the shift.”

Remote infrared thermometers are already used in airports to detect fevers (Credit: Julio Cesar Aguilar/Getty Images)

His team has already compared the device’s performance against the standard swab tests on 150 patients and found it was 92% accurate. That’s pretty high, Sarusi notes, given that many approved medical tests have lower accuracy than that. However, because the breathalyser results will have high stakes – travellers may be denied boarding or quarantined – the team wants to improve the device further. Once it’s ready, they hope to get an expedited approval from the FDA because it could revive the travel industry. Sarusi expects the machines to start appearing in airports and train stations soon. “Maybe by the end of this year. Or next year,” he said.

You may also be interested in:

• The Dutch islands of tomorrow

• Rebuilding the world's northernmost town

• The island with a key to our future

Of course the best thing to put everyone’s worries to rest would be a vaccine. Experts think the vaccine may become available in 2021, as reported in Scientific American, so those travelling would have to keep their vaccination records. Even today, some countries require proof of recent vaccination for diseases like yellow fever, and the coronavirus may join that list.

Travellers would present the customs officers with an entrance visa and a vaccination record. That could be a paper card – or a tiny tattoo on their arm, invisible to the naked eye but readable by an infrared scanner. This technology already exists and has been tried on live animals and human cadaver skin, said researcher Ana Jaklenec at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Their method uses micro-needle patches that can deliver both the vaccine and a squirt of an invisible ink under the person’s skin, storing the vaccination record.

Professor Sarusi expects his device to start appearing in airports and train stations soon (Credit: Courtesy of Ben-Gurion University)

“The macro-needles don't leave scars and are less invasive than the regular needles – it’s like putting on a Band-Aid,” Jaklenec said. That subdermal record is readable by a simple scanner, she added. “It can even be done with a modified phone.”

Supported by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the technology was aimed to help in the developing world where paper or electronic records aren’t always reliable. The goal is to try it on humans with a measles vaccine soon, but the tech may come handy for other proofs of immunisations – for example at the immigration point.

After finding your passport and proceeding to immigration, an officer greets you. Now it’s time to get your bag. At the carousel, a worker offers to spray your luggage with some smelly industrial sanitiser, but you politely decline. Instead you pop out a bottle of an eco-conscious Veles cleaner scented with bergamot, lavender and mint – an aroma that can soothe the worst jetlag.

Although temperature checking is helpful, travellers can have fevers for others reasons or may harbour coronavirus without symptoms (Credit: Pixinoo/Getty Images)

Developed by Amanda Weeks, who grew up on Staten Island next to New York’s infamous rubbish dump, Veles is made from food waste that’s fermented akin to a brewing process, yielding alcohol. “It’s like making kombucha or beer,” said Weeks, who opened a pilot bio-refinery plant in 2018, aiming to divert truckloads of leftovers from landfills and reduce the amount of rotting food and the greenhouse gases it emits.

Currently Veles is designated as a household cleaner and not a sanitiser because Weeks hasn’t put it through the EPA-required tests (sanitisers kill microorganisms so they’re considered pesticides and must be approved by the EPA). “Only a handful of labs can do that and they charge six figures for the tests,” Weeks explained, but she plans to do it as soon as she has the money.

With sweet-smelling, clean bags, you proceed to the taxi stand. In the meantime, the aeroplane you disembarked from is also being disinfected – by GermFalcon. A lean, mean, ultraviolet light cleaning machine, GermFalcon was built by father and son Arthur and Elliot Kreitenberg, frequent flyers turned citizen scientists. A medical doctor, Arthur Kreitenberg knew aeroplanes can spread disease; they’re notoriously difficult to clean because of tight schedules, flight delays and hard-to-reach nooks and crannies. He also knew that hospitals use UVC lights to disinfect surfaces and instruments.

GermFalcon shines UVC light onto aeroplane tables and seat cushions to kill germs (Credit: GermFalcon)

There are three types of ultraviolet light: the milder UVA and UVB present in the sunlight, and the more damaging UVC, which is filtered by the Earth’s atmosphere and has the ability to destroy germs’ DNA. So the father-son team built a UVC machine that can be wheeled through the planes’ aisles, shining the germ-killing light onto the tables and seat cushions.

It became more of a necessity than luxury

With its slender cart-like body and two “wings” spread over the rows of seats, GermFalcon indeed looks like a bird of prey and can disinfect a Boeing 737 in less than five minutes. “We recommend doing 30 rows per minute,” said Elliot Kreitenberg. “At that rate we can provide the 99% of reduction of influenza and coronavirus.” The two have worked with professional labs to test the results. GermFalcon will start “hunting” germs on aeroplanes later this year, he added.

“UVC light is used for disinfecting in a lot of applications and is a pretty effective disinfectant,” said Andrea Silverman, assistant professor at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering and College of Global Public Health. “And it works well for bacteria and viruses,” she added, as long as the organisms receive enough of the light, which most UVC devices are able to produce.

UV-cleaning devices may also become commonplace in disinfecting hotels, cruise ships and taxis, so when you climb into one you don’t have to worry about the germs in the air. As you read the driver your hotel address from your smartphone, you realise how dirty the screen is. When was last time you cleaned that thing? Probably on the plane, hours ago. Meanwhile, you’d put it down at the customs counter and the vaccine scanner, so it’s also due to be sanitised.

Comments

Post a Comment